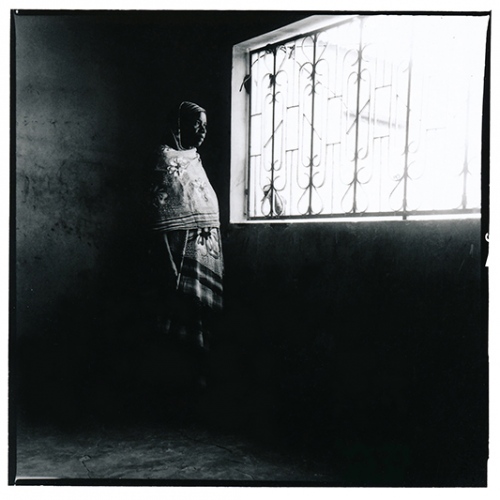

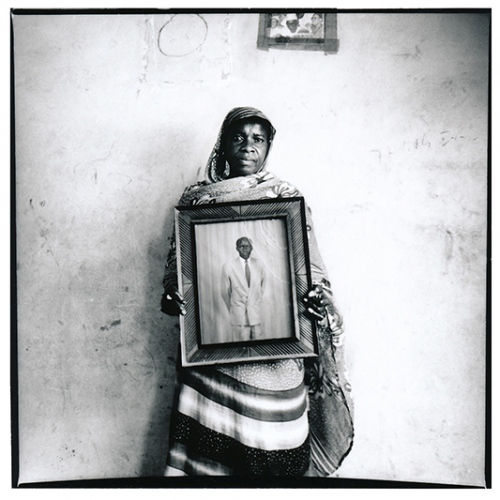

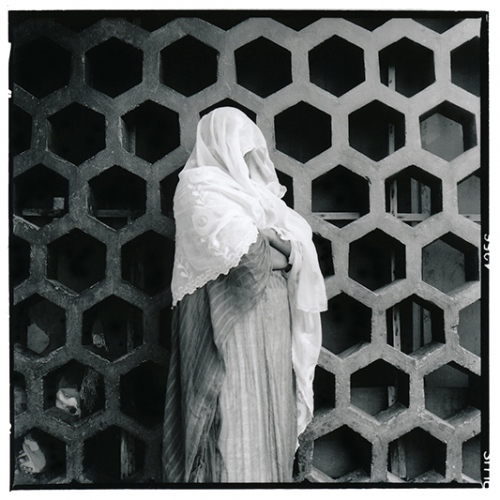

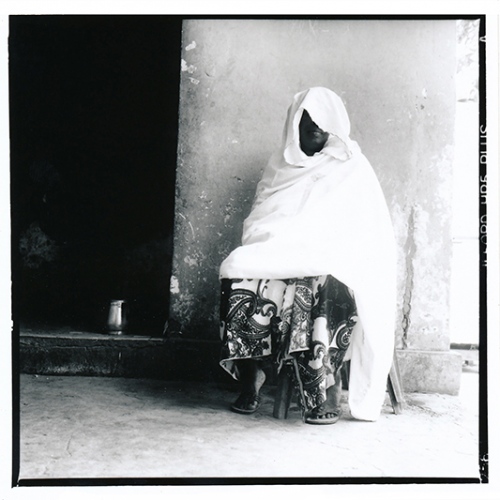

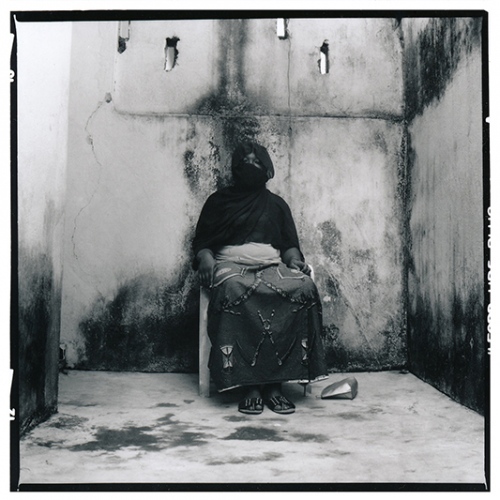

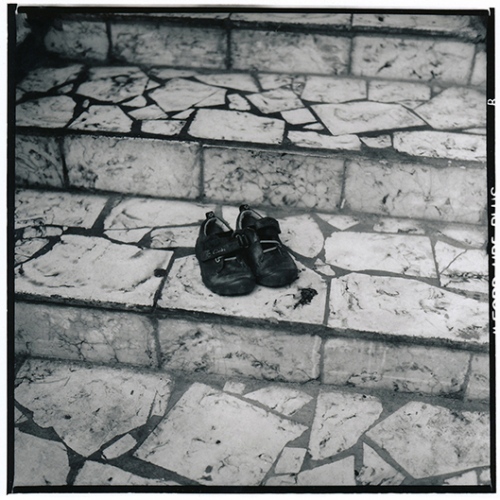

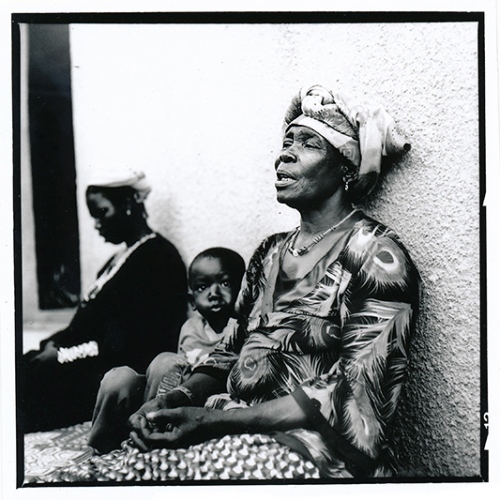

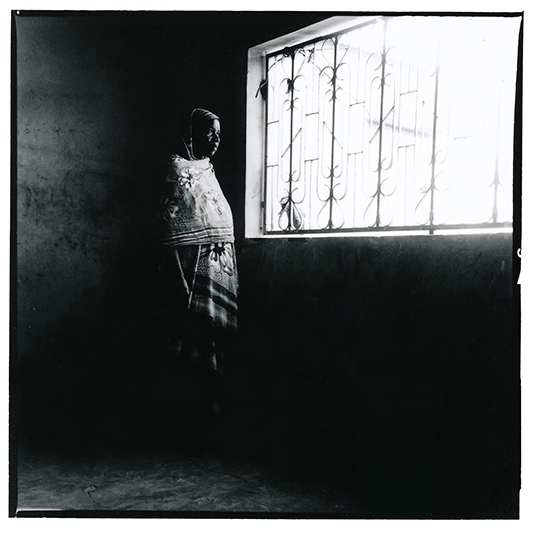

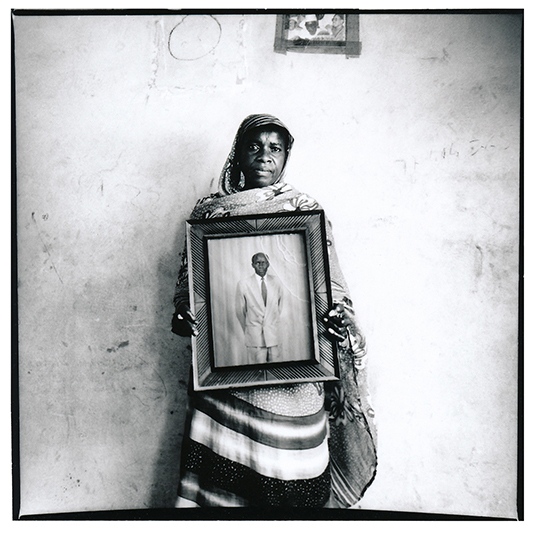

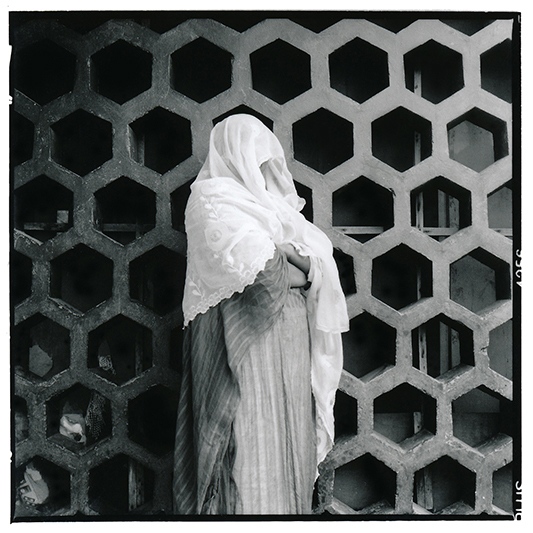

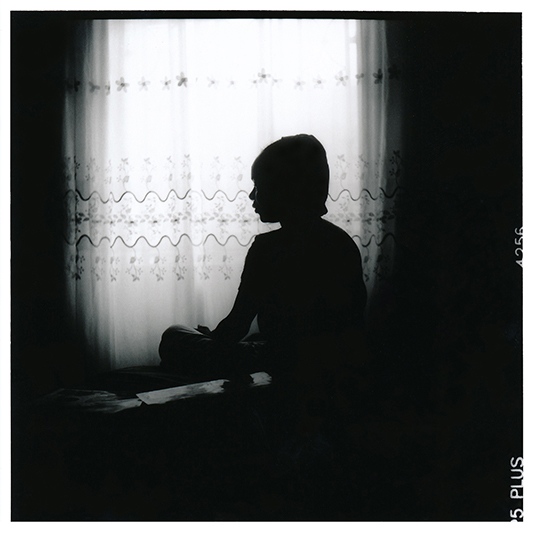

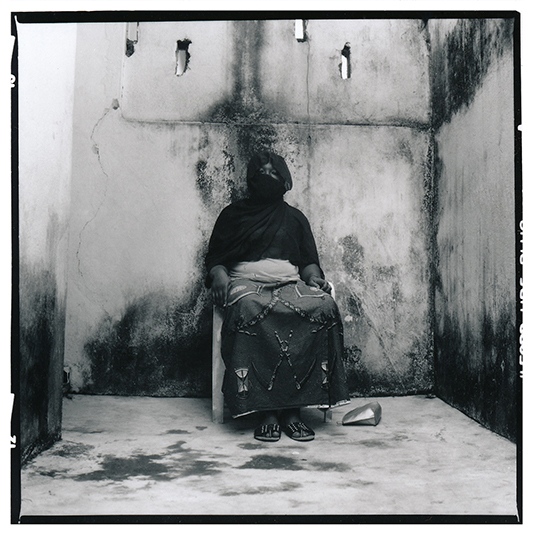

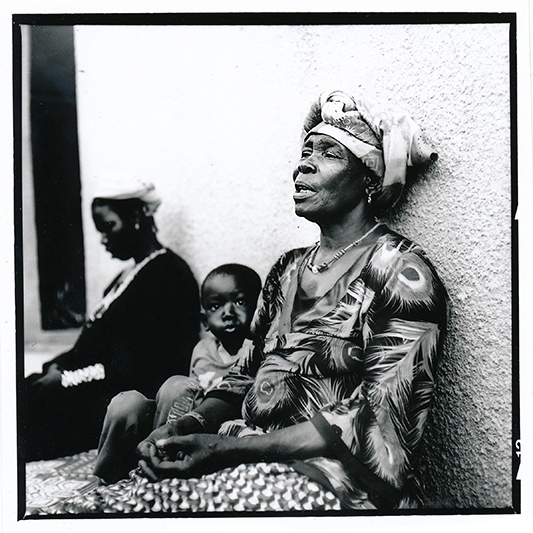

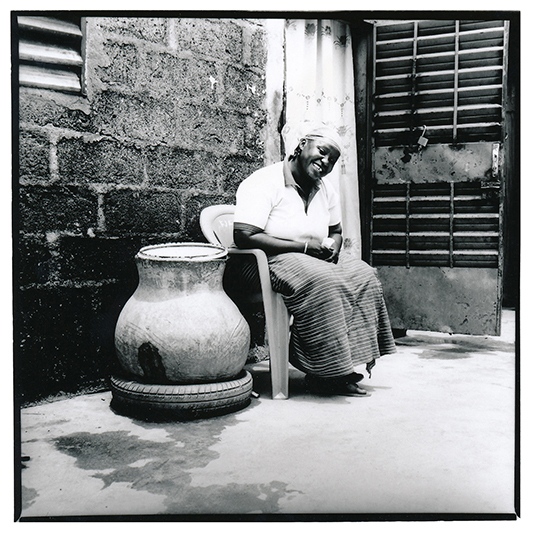

How do you photograph the act of waiting? How do you make pictures of separation, expectation, longing? How do you shed light on one of the hidden faces of international migration – the wives in waiting - while respecting the privacy of those who have stayed behind and are often reluctant to be seen?

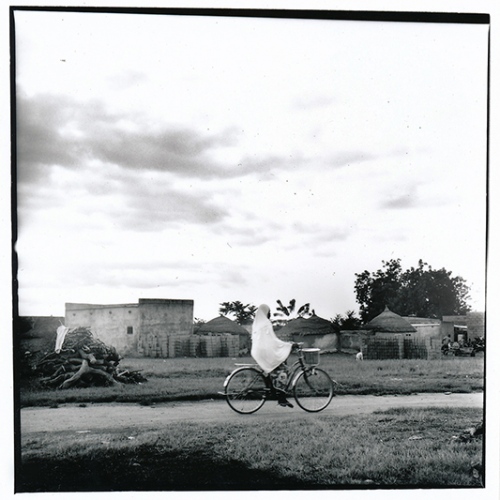

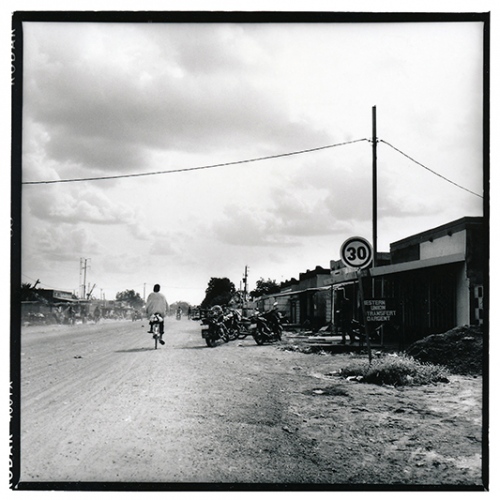

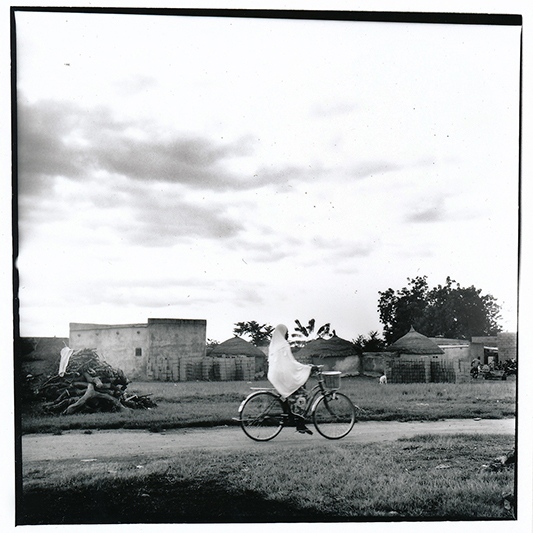

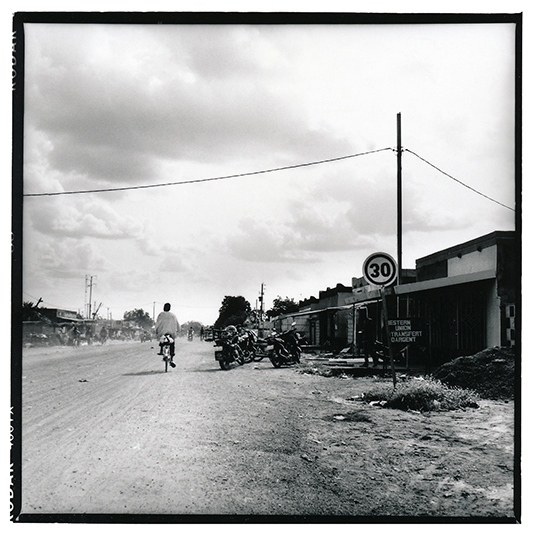

Before anything else, you have to explain and earn trust. You have to repeat over and over again to Cumba, Ndeye, Fanta, Alimata and so many others that their voices and their stories. At first, many of these wives thought they would join their migrant husbands. They are called 'Modou Modou' in Senegal or 'Benguiste' in Ivory Coast - African men who left for Europe in search of better prospects. You've seen the most unfortunate ones on the news. The ones who drown at sea during the travel.

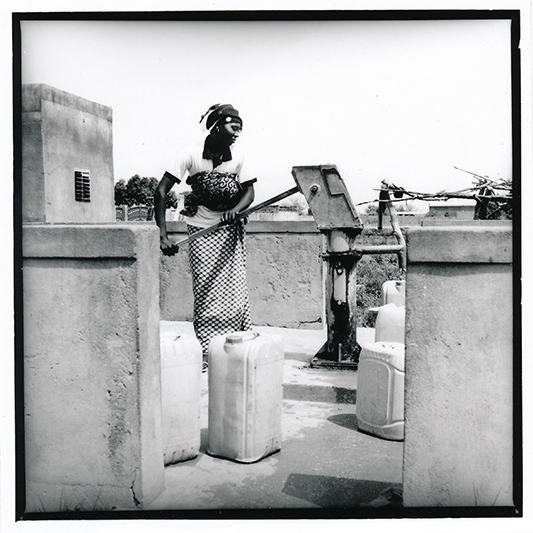

Before their departure or as they settle on the other side, many of them get married in their community or village of origin. Countless girls and families from a poor or rural background believe that marrying a migrant bears the promise of a wealthier life.

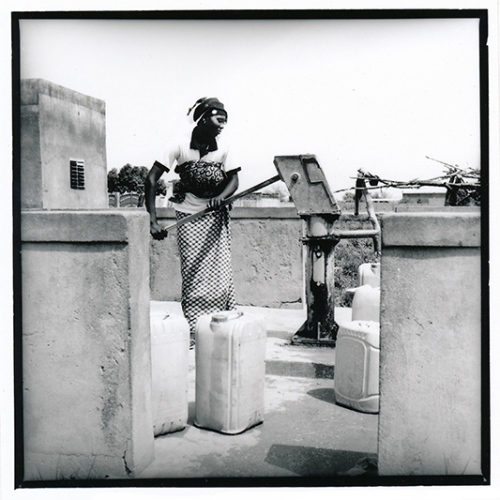

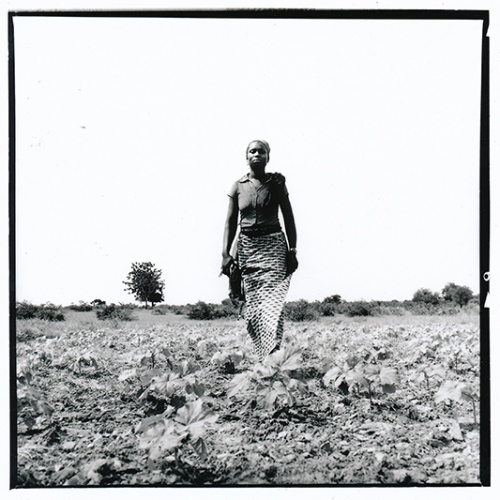

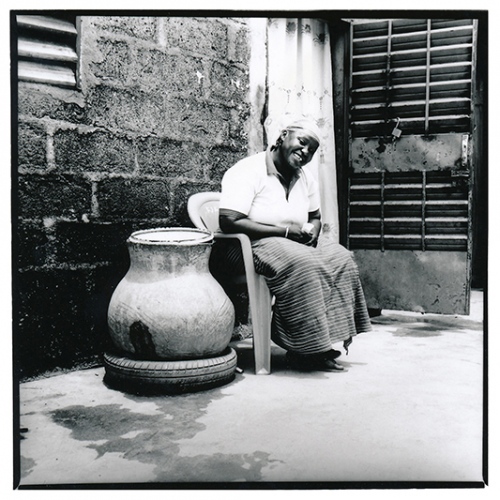

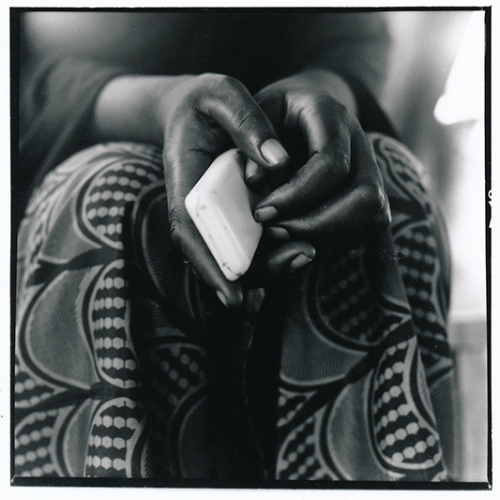

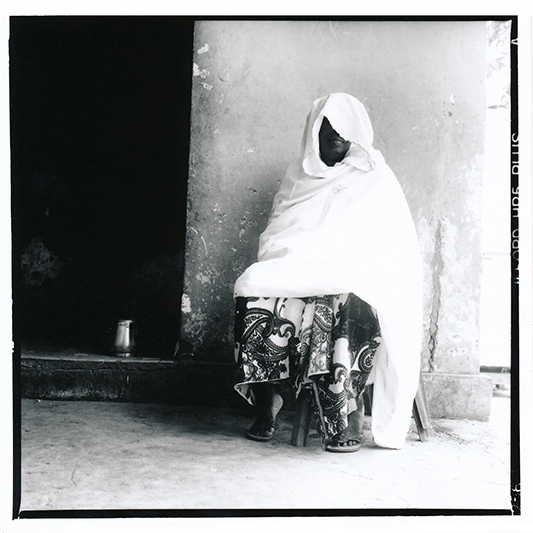

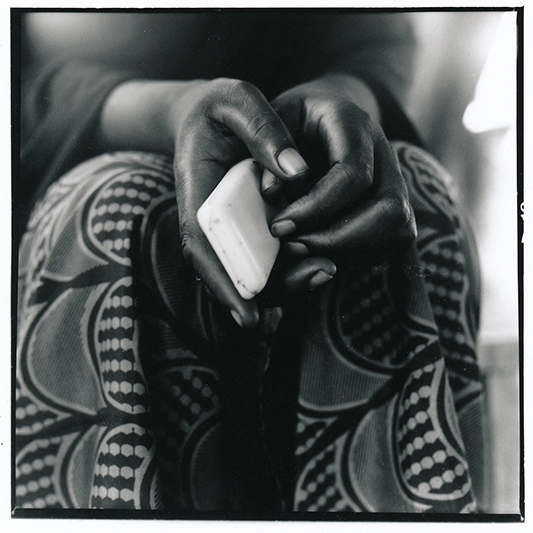

Most of the migrants' wives I met initially believed in their good fortune. But in time, many have had to silence their dreams. Left behind in their husbands’ families, they can only travel via a proxy. The photo series 'Such long nights' tells the story of women entrapped in a no man's land. Faces and places in tales of constant waiting.

Photographing African spouses waiting for the return of their men is not just about portraying disappointment and victims. The most striking parts are not the truncated lives, unfulfilled hopes and rusty dreams. It is the resilience. The self-irony. The dignity of women who hold their sense of humour as if it were steel armour.

Analog photography. Louga, Senegal, Abidjan, Ivory Coast, Beguedo, Burkina Faso, 2015 - © Laeïla Adjovi